The 19th century saw the professionalization of the historian along with the development of the nation-state as the world’s dominant political structure. Centralized governments turned to narrative of history as a way to mold a collective identity and stimulate nationalism among a diverse citizenry. Historians produced a version of the past that elevated to the level of national canon which could be learned in schools and glorified through cultural manifestations. National histories motivated citizens to fight (and die) for the nation. Immigrants could be taught the new national identify. Hierarchies of national-cultural types produced “authentic” and “real” versions of what the nation stood for.

The 19th century saw the professionalization of the historian along with the development of the nation-state as the world’s dominant political structure. Centralized governments turned to narrative of history as a way to mold a collective identity and stimulate nationalism among a diverse citizenry. Historians produced a version of the past that elevated to the level of national canon which could be learned in schools and glorified through cultural manifestations. National histories motivated citizens to fight (and die) for the nation. Immigrants could be taught the new national identify. Hierarchies of national-cultural types produced “authentic” and “real” versions of what the nation stood for.

Globalization (along with post-modernism) has challenged the purpose of historical scholarship and problematized the narratives they produced. In turn, the late 20th century expanded how history is done and taught. The expanding purpose of history and rejection of the singular national narrative democratized historical, and contemporary, agency. The earlier conceptions of identity, culture, and history based on the nation and reinforced as natural phenomenon bestowed upon citizens at birth, immutable, and essentialized was no longer a valid worldview.

Now, in the 21st century, nationalism finds itself supplanted by the realities of an interconnected planet. Today’s emphasis on globalization, global systems, and world power players other than the nation-state, requires history education to prepare students with global competencies to develop skills, think critically, act intelligently and be poised for success in contemporary society and the future.

Simply put, teaching a traditional national U.S. narrative to students limits students’ educational potential by using an outdated model and purpose for education. The American Council on Education notes, “A 21st Century Imperative makes the case that U.S. global competence in the 21st century is not a luxury, but a necessity. Whether engaging the world, or our culturally diverse homeland, the United States’ future success will rely on the global competence of our people. Global competence must become part of the core mission of education—from K-12 through graduate school.”

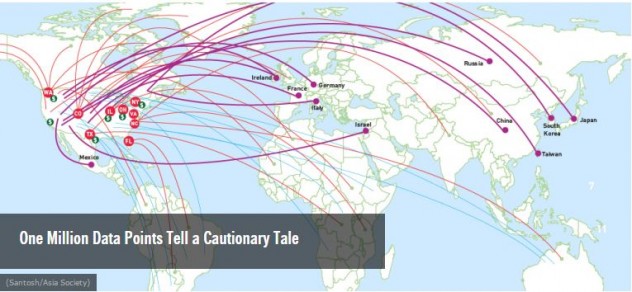

Additionally, the Asia Society and Longview Foundation partnered to create the dynamic resource “Mapping the Nation.” Mapping the Nation is an interactive map that pulls together demographic, economic, and education indicators—nearly one million data points—to show that the United States is a truly global nation. Explore the resource and make the case for globalizing your U.S. history course. If you find your district/state is not globalized… then you should get started. If you conclude your district/state is globalized, then keep the movement going and provide a global perspective for your students.

Lastly, A major inspiration for this project was the 2000 La Pierta Report. The report welcomed the 21st century with a challenge to U.S. History educators everywhere:

“National history remains important, and will of course continue to be so in the future. But the national history we are describing resituates the nation as one of many scales, foci, and themes of historical analysis…We believe that there is a general societal need for such enlarged historical understanding of the United States. We hope that the history curriculum at all levels, not only in colleges and universities but also in the K-12 levels will address itself to these issues… It is essential that college and university departments–which carry the responsibility for training historians who will teach at the K-12 levels–begin this work of integration.”

Globalizing history education, therefore, involves an “opening” of students’ conceptions of the past through expanded content, broader methodology, and units of analysis that go beyond the nation. Preparing history teachers to do this is integral to the longevity and success of global education. This project addresses gaps in thought leadership and the scarcity of resource dedicated to globalizing the U.S. history survey.